|

Caroline Clemens: A Scleroderma Story This article originally appeared in the Winter 2011 issue of "Scleroderma Voice."

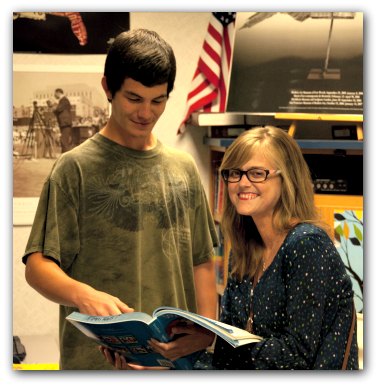

In March 2010, Caroline rushed to the emergency room because she had a fever and worried that her continuous IV line might become infected. So weak that she couldn’t walk on her own, Caroline’s father Jack had to carry her in. Shortly after arriving at the hospital, she suffered a stroke. What should’ve been a quick, routine visit for the young teacher left her in the dark for two weeks. “When I woke up, my mom said I had a stroke,” Caroline recalled. “It really startled me. I lost two weeks of my life. I just didn’t remember any of it. When I came to, I didn’t even remember what year it was.” For Caroline, that startling experience always lingers in the back of her mind – a “what if…?” Her doctors couldn’t determine what caused the stroke because of a myriad of other health issues that had begun to crop up in the preceding years. Fortunately, the stroke didn’t leave her paralyzed. However, she needed therapy to work on her handwriting, memory and speech; plus, physical therapy to regain her strength and relearn basic tasks such as brushing her teeth and showering. “I Thought It Would Just Go Away” Caroline started to notice subtle changes while waiting for a ferry on a trip to San Francisco in 2003. She had trouble doing simple, everyday tasks like opening a bottle of soda. She returned home to Texas to begin her third year of teaching thinking nothing was amiss. Soon, she had trouble combing her hair or holding her hair dryer, and turning her car’s steering wheel became a painful task. “I didn’t quite know what was going on,” she said. “I’m a tough person so I thought it would just go away.” Caroline visited her primary care doctor, who referred her to a rheumatologist. After a few months had passed, they decided her symptoms were caused by arthritis. At 23, Caroline listened to the doctors and added some new medication to her daily routine. Over the years, her skin began to tighten. Bits of skin on her arms and legs started to look scaly. Her scleroderma diagnosis would come two years later. “Caroline had been misdiagnosed by other doctors before being diagnosed with scleroderma,” said her father Jack Clemens. “We just thought scleroderma was a big name for a skin rash. We had never heard of it. We didn't realize how serious it was.” Through all the difficult news and diagnoses, she saw a bright spot. Caroline loved working as a teacher at Allen High School, connecting with students and passing along her adoration for writing and learning. Life was great except for the few pills she needed to take here and there. The Ups and Downs of Scleroderma In 2007, everything escalated. Climbing the stairs to her second floor classroom became a Herculean undertaking. Even walking to the front of her classroom left her breathless. At home, doing the laundry, tying her shoes and dressing herself – all ordinary tasks – took the wind right out of her lungs. Now under the guidance of a new rheumatologist, Caroline went through a series of tests – pulmonary function, echocardiogram, cardiac MRI and right heart catheterization. The results came back and showed she had developed pulmonary hypertension as a result of scleroderma. She started a regimen of even more pills and a clinical trial to combat this new struggle. The clinical trial medications left her severely underweight, leading her to need a continuous IV. Finally, life was good again. She had more energy; she could breathe; she could walk. Most of all, she loved teaching again. Sadly, Caroline’s health turned for the worse again at the beginning of the 2009 school year. She spent 43 days at the University of Texas Southwestern Medical Center. Her kidneys had failed and she needed dialysis 10 hours each night. The process was tedious and tiresome. Caroline inserted a warm liquid into a catheter in her stomach. After two hours, she flushed the liquid and the cycle began again, four more times. Caroline pushed herself to return to the classroom in January 2010 but lasted only a few months until her stroke. Doctors told her the only solution would be a kidney transplant. Finding a team to perform an organ transplant on someone with scleroderma was difficult. Eventually, she found doctors at the University of Pittsburgh willing to help. Miraculously, Caroline would never need their services. Her kidney functions began to normalize, and today, she has about 30 percent of her function back and she’s off dialysis. “Doctors will look at me sometimes and they say, ‘What? How is this possible?,’” Caroline said. “They don’t understand my case because it’s just so rare to see people who eventually don’t need dialysis anymore.” Community Comes Together for a Cause Despite struggling through health concerns, Caroline continued to teach. In 2008, Allen High School named her Teacher of the Year. Then, the following year, while in the hospital, she received an amazing phone call. “My boss called me while I was in the hospital. She told me more than 325 people nominated me to be the recipient of our school district’s fundraising and awareness campaign,” she said. “It was so flattering and overwhelming that the entire community could come together for this one cause.” The students and faculty in the Allen School District raised $18,000 to cover Caroline’s health care costs as part of “Love Week,” an initiative that selects a cause based on nominations. They made posters and public service announcements to educate the entire community about the disease. “I wear a purse around my waist that houses my continuous IV. I see the looks on some of the kids’ faces. They are so shy. I know they want to say something,” she said about how she initiates talking about scleroderma. “I usually spend about 45 minutes each semester with my students discussing the disease. We talk about the origins of the word, kidney failure, pulmonary hypertension, everything about scleroderma. The students are extremely receptive and listen to every word I say.” Caroline is asked all the time, “How do you do it?” Her reply is simply, “Because I have to.” She wouldn’t trade a thing for the life she enjoys – teaching an exceptional group of young people every day, shopping with her sisters on Saturday and going to church on Sundays. “To go through everything I have gone through, it makes me thankful for every little thing,” she said. |

|

|

Back

Understanding Scleroderma

Back

Treating Scleroderma

Back

Living Well with Scleroderma

Back

Advancing Research and Treatment

Back

Get Involved

“Life is essentially a cheat and its

conditions are those of defeat; the redeeming things are not happiness and

pleasure but the deeper satisfactions that come out of struggle,” wrote F.

Scott Fitzgerald in a letter to his daughter in 1940. The American

author, best known for his novel “The Great Gatsby,” is one of Caroline

Clemens’ favorite writers. The 32-year-old high school English teacher from

Richardson, Texas, has overcome numerous struggles since being diagnosed with

scleroderma and pulmonary hypertension.

“Life is essentially a cheat and its

conditions are those of defeat; the redeeming things are not happiness and

pleasure but the deeper satisfactions that come out of struggle,” wrote F.

Scott Fitzgerald in a letter to his daughter in 1940. The American

author, best known for his novel “The Great Gatsby,” is one of Caroline

Clemens’ favorite writers. The 32-year-old high school English teacher from

Richardson, Texas, has overcome numerous struggles since being diagnosed with

scleroderma and pulmonary hypertension.